The Background Illustration

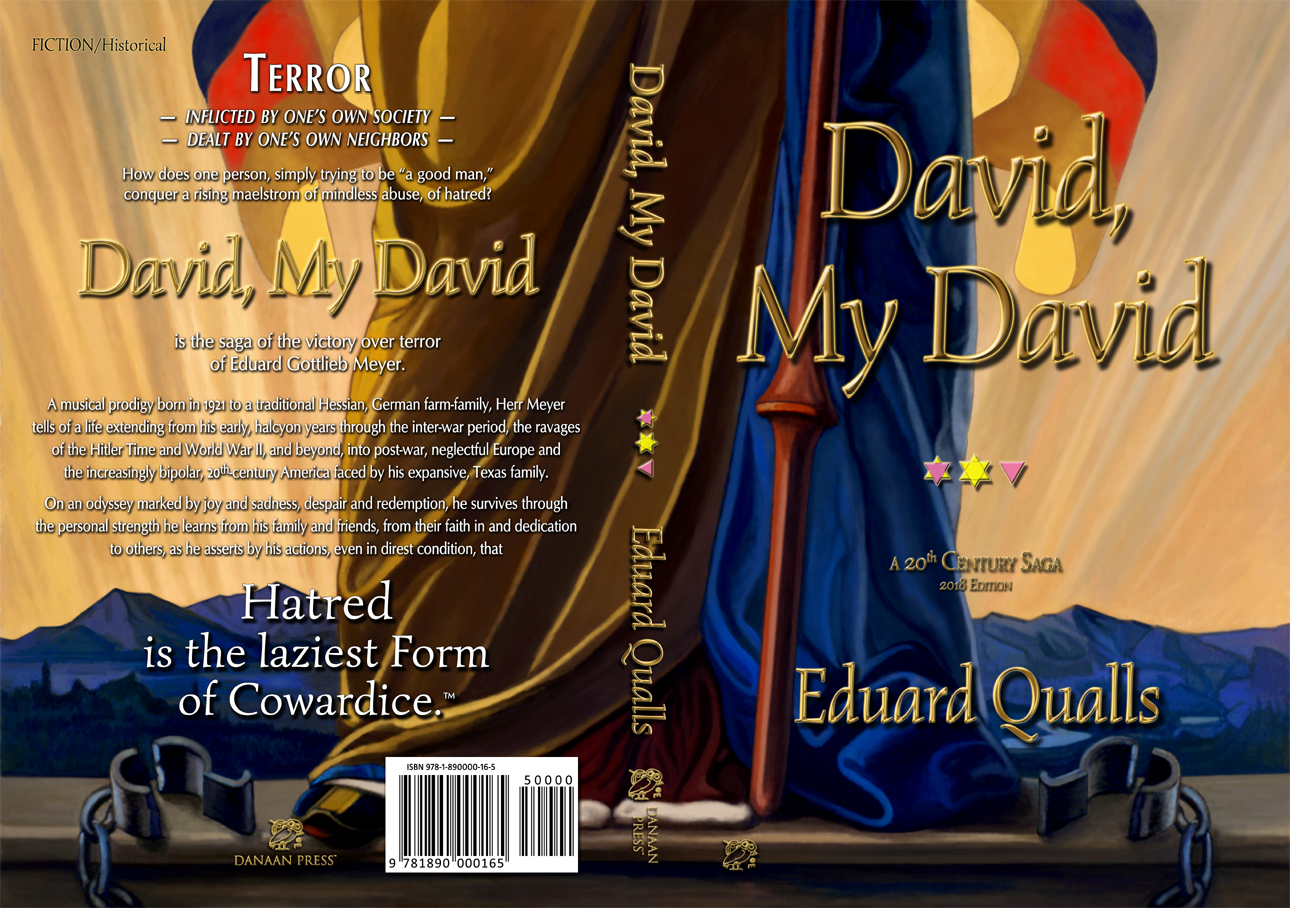

The image that forms the background of the cover, and of this website, is a drawing based on the bottom third of a painting that was at the core of a most important period within modern German history.

That painting is Philipp Veit’s metaphorical image of » Germania « that hung prominently before the assembly in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt am Main during 1848-49, looking down upon those delegates who were meeting there, striving to forge a constitution through which they might unite the very numerous German states—the baronies, free cities, prince-bishoprics, duchies and kingdoms—within a republic. However, this attempt to form a republic in the form of a constitutional monarchy was quashed violently by the combined conservative forces of the Austrian Emperor, the King of Prussia, the monarchists, the princelings and the Church.

»Germania« by Philipp Veit, as restored by the author, Eduard Qualls.

There can be little doubt that, if this assembly had succeeded in unifying Germany at that time, there would have been neither of the World Wars, and that if its efforts against Antisemitism had prevailed, there would have been no Holocaust.

Veit’s painting is the currently most prominent, extant occurrence of the black-red-gold flag that, by 1832, had come to symbolize a free, liberal and democratic Germany in the struggle against the Conservative Order imposed on Europe after the defeat of Napoleon.

After the Revolution of 1848 was murderously suppressed, the black-red-gold flag was forced out of use quickly. (Only three tiny principalities retained it.) By the time the German Empire was established in 1871, that flag had been completely eradicated by the red-white-black dreariness of the flag of the North German Confederation, and this flag and color-scheme was retained throughout the years of the Empire.

In 1919 the black-red-gold flag was chosen by the German Republic founded in Weimar, and was seen (as referenced in the text by Edi’s grandmother) as a symbol of democratic government, fighting off extremist, conservative oppression: the monarchists, the fascists and the communists. But the Nazis outlawed it in March 1933, re-instituting the Empire’s black-white-red banner until that was replaced by the Nazi Party’s own red, white and black, the swastika flag, in August, 1935.

The black-red-gold flag, having become so potent a symbol of liberal democracy, was restored to national use in 1949, with the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany. In 1989 it became the unencumbered symbol of the reunified German Republic.

The power of this flag’s significance as a symbol of freedom is revealed in the fact that, even now, it remains under attack from neo-Nazi conservatives.

[Those particular adaptations made here to Veit’s original painting, aside from simplification of design, are the broken shackles, copied from the left-hand side and duplicated on the right; and the flag, mirrored onto the left-hand side from the original’s right.]

The Badges

![]()

These three symbols are just some of the many badges used within the extensive prison- and death-camp system set up by the Nazis to exterminate all opposition to their maniacal regime.

The center, yellow one is the un-labeled Star of David, as used within the camps. The pink one on the right designated non-Jewish homosexuals, while the one on the left combines the upwards-pointing triangle of the Jewish star with the homosexual triangle brought forward, targeting the wearer for the greatest abuse.

A full exposition of the Teutonically efficient badge-system is located here.